Substance use disorders (SUD) are common in patients with bipolar disorder, but they complicate the diagnosis and optimal treatment of this mood disorder. During a virtual educational webinar called “Improving the Lives of Patients with Bipolar Disorder” offered by the Neuroscience Education Institute (NEI), Dr. Joseph Goldberg, a Clinical Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, encouraged clinicians to ‘always have a detective mindset’ when approaching the management of comorbid substance use and bipolar disorders.

Diagnostic dilemmas

One of the cornerstones for establishing a diagnosis of bipolar disorder is to exclude the presence of a substance as a causative factor in an acute episode of mania, hypomania, or depression. Indeed, one of the four DSM-5 criteria for bipolar disorder is “The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication or other treatment) or to another medical condition.”1 This is because the physiological and/or psychological effects of substance use can mimic psychiatric disorders including bipolar disorder.

The presence of an active SUD reduces the reliability of screening tools for bipolar disorder, with positive predictive values dropping down to 25–30% in the presence of one disorder and 20–22% when there are two or three substances.2 This should not dissuade clinicians from screening a patient for bipolar disorder if they have a suspicion that it could be part of the clinical picture, but they should be aware that it could be more difficult to confirm the diagnosis.

Substance use impedes the reliability of screening tools and complicates the diagnosis of bipolar disorder

Another conundrum for clinicians is distinguishing between substance use versus SUD. Red flags that suggest an SUD rather than substance use include the presence of cravings, difficulty controlling consumption, neglecting other aspects of daily life, and continued use despite negative consequences of using the substance.1 It is important for clinicians to have a heightened suspicion of SUD in patients with mood disorder including bipolar disorder since the prevalence of SUD is disproportionately higher than in the general population. According to a large U.S. epidemiological study on alcohol use and related disorders, people with bipolar I disorder were 1.5 to 2 times more likely to have an alcohol use disorder than the general population.3 Other epidemiologic studies suggest similar trends for other substances including cannabis, stimulants, cocaine, sedatives and opiates.4,5 Dr. Goldberg likes to share these statistics with his bipolar disorder patients so that they can be ‘informed consumers’ and understand that they have a higher vulnerability to SUDs than the average population.

Patients with bipolar disorder are 1.5 to 2 times more likely to have an SUD than the general population

Comorbid SUD has myriad negative consequences in patients with bipolar disorder

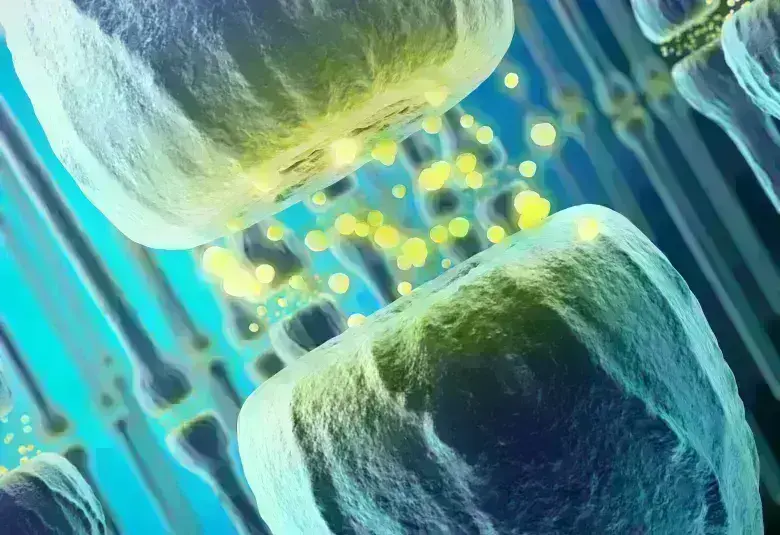

Not surprisingly, the co-occurrence of SUD with bipolar disorder is associated with poorer outcomes including poorer response and adherence to treatment of bipolar disorder, increased hospitalizations, higher risk of suicidality, and poorer neuropsychological and cognitive functioning, especially in attention and executive domains.6,7 A recent study examining the impact of SUD on brain structural connectivity in bipolar disorder offers a provocative hypothesis on why the bipolar brain might be ‘hard wired’ to be at risk for substance use and abuse.8 It suggests that people with bipolar disorder have increased connectivity in the paracingulate gyrus and decreased connectivity in an executive control network compared to individuals without bipolar disorder, and this could make them more prone to externally focused emotional regulation. Dr. Goldberg summarized that in individuals with bipolar disorder, their thoughts drift towards use of substances more easily when they have mood lability and become less capable of applying healthier approaches to emotional regulation.

Bipolar disorder is associated with neurocognitive brain changes that increase vulnerability to substance use

Considerations for managing concurrent SUD in patients with bipolar disorder

Dr. Goldberg underscored the importance of psychoeducation to help patients with bipolar disorder make informed decisions, and this is particularly imperative in patients with comorbid SUD. He advocated for educating patients in a non-judgmental manner about self-care and vulnerability models to make them ‘informed consumers’ and for establishing an accurate diagnosis since ‘the right diagnosis often leads to the right treatment.’ Notably, formal behavioural interventions such as integrative group therapy, which was specifically developed for this ‘dual diagnosis’ population, have been associated with reductions in substance use in patients with comorbid SUD and bipolar disorder.9 Some – but not all – mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics, notably the partial dopamine agonists, have shown benefit in reducing substance use in patients with bipolar disorder, but the studies are generally small and require replication in larger cohorts.10

Bipolar disorder patients should be aware of their increased vulnerability to SUD so they can make informed decisions

Our correspondent’s highlights from the symposium are meant as a fair representation of the scientific content presented. The views and opinions expressed on this page do not necessarily reflect those of Lundbeck.