A dedicated session at the 2023 Canadian Neurological Sciences Federation congress that was held last June 7th in Banff, Alberta focusing on the important relationship between female sex hormones and migraine. This symposium was titled " Hot Topics in Neurology: Pills, Pregnancy and Patches: The Relationship between Hormones and Migraine."

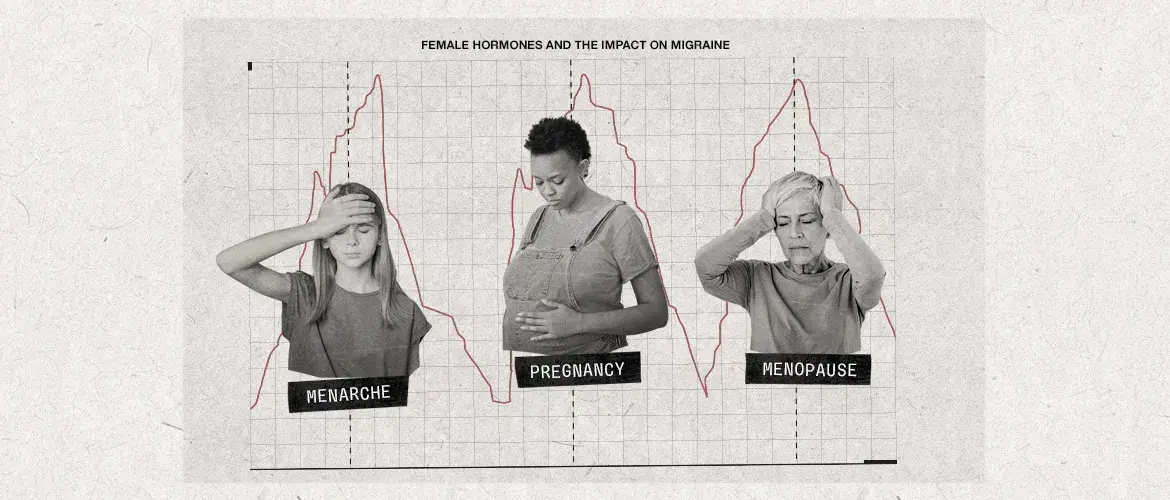

During this session, renowned Canadian experts in the field of headache presented on a variety of subjects linking female sex hormones to migraine throughout a woman’s life. Because these hormones fluctuate notably at menarche, menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause, emphasis was placed on these specific timepoints.

Role of hormones in migraine

During the first presentation, Dr. Farnaz Amoozegar (University of Calgary) and Dr. Ana Marissa Lagman-Bartolome (University of Toronto) mentioned that, in addition to being more than three times more prevalent in women,1 the cumulative incidence of migraine in women remains 2-3 times higher compared to men throughout their reproductive years.2 These observations strongly suggest a connection between female sex hormones and migraine. Therefore, clinicians should consider these sex-based differences when managing patients with migraine.

These observations strongly suggest a connection between female sex hormones and migraine.

Relationship between menarche and menstrual migraine in teens

Pediatric migraine is a common condition, with up to 10% of children experiencing migraine.3 Dr. Thilinie Rajapakse (University of Alberta) highlighted that one-third of women with migraine reported that their first attack and their first menstrual period occurred around the same time.4 Combined with the fact that the risk of developing migraine increases with age until puberty,3 these findings suggest a role of sex hormones in the disease’s etiology.

Pediatric migraine is a common condition, with up to 10% of children experiencing migraine.

Migraine in pregnancy and lactation

Important considerations on migraine in pregnancy and lactation were also covered. On this topic of great interest among migraine caregivers, Dr. Michael Knash (University of Alberta) discussed the risks associated with various acute migraine rescue medications. Dr. Knash also reported published findings from a pregnancy registry that monitored for a signal of major teratogenicity in the offspring of women taking certain triptans during pregnancy: among exposed infants and fetuses, there was no increased risk of major birth defects.5

Understanding and treating migraine in perimenopause and menopause

This surge in migraine impact can be explained by the high fluctuations in estrogen that are frequently observed during perimenopause.7

During the final presentation, Dr. Farnaz Amoozegar explained that, while migraine frequency and severity usually decrease during menopause, they often increase during perimenopause.6 This surge in migraine impact can be explained by the high fluctuations in estrogen that are frequently observed during perimenopause.7

Because migraine is a risk factor for ischemic stroke that is further increased by oral contraceptive use, particularly in those who experience migraine with aura,7 Dr. Amoozegar recommended to avoid the use of oral estrogens for patient with migraine with aura. She also reported that there is no clear evidence for a treatment benefit on migraine for post-menopausal hormone replacement therapy.7

Importance of the relationship between female sex hormones and migraine to better treat Canadian women affected by migraine

Given the high prevalence and incidence of migraine among women1-2 and its significant impact on quality of life,8 increasing attention and awareness concerning the relationship between female sex hormones and migraine is of particular importance to better treat Canadian women affected by migraine.

Our correspondent’s highlights from the symposium are meant as a fair representation of the scientific content presented. The views and opinions expressed on this page do not necessarily reflect those of Lundbeck.