Social media platforms such as TikTok have seen a steep rise in use in recent years, particularly among young people. Researchers from the Department of Psychiatry at Queens University in Kingston, Ontario, explored the links between mental illness appropriation on TikTok and self-diagnosis particularly among youth during a poster presentation at the annual Canadian Psychiatric Association (CPA) conference in Vancouver in October, 2023.

The meteoric rise in social media use

Social media has been a rapidly evolving landscape, and recent estimates suggest that there are now over 1.5 billion monthly users of TikTok worldwide, one of the most popular social media platforms.1 Although young people are the largest demographic using TikTok (nearly two-thirds of users are aged 10 to 29 years),1,2 a growing number of adults are also using the platform as a primary source of news.3

The majority of TikTok users are under 30 years of age

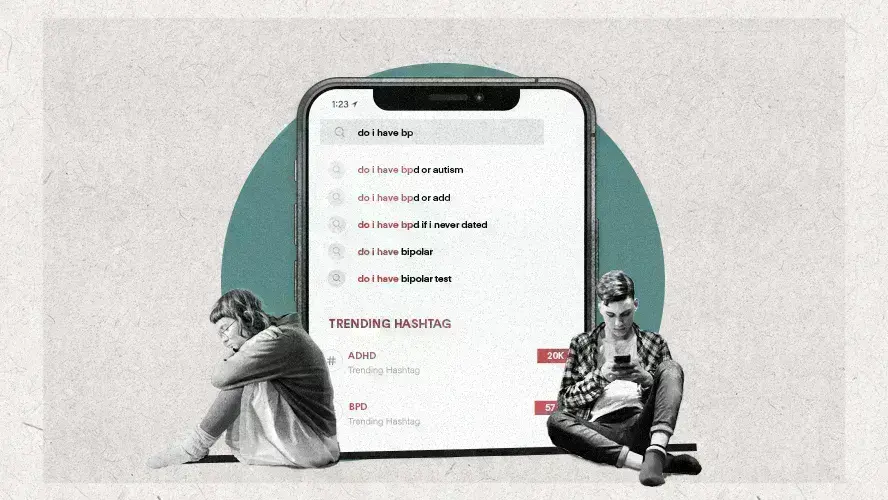

Mental health posts on TikTok

Social media platforms have become an important outlet for young people to share experiences with a community of peers, and many videos have portrayed individual struggles with mental health issues.2 Indeed, according to the poster presented by Imaan Javeed & Ahila Vithiananthan from Queens University, some very popular hashtags include #ADHD (attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder; 31.2 billion views), #BPD (borderline personality disorder; 11.7B views), #tourettes (9.5B views), and #DID (dissociative identity disorder; 3.1B views). Yet some of these disorders, particularly DID, are relatively rare diagnoses and youth may be posting their personal experiences based on self-diagnosis for secondary gains with respect to peer support, recognition, and a sense of belonging.4 Moreover, a tendency to performative sick-role videos that often showcase symptoms as being ‘cute’ or comical has been observed and reported in the medical literature, and has led to concerns that social media may be serving as a vector for reinforcing the escalation of symptoms and even simulation of symptoms of factitious disorders.2,4

Social media can help destigmatize mental illness but also perpetuate misinformation

Factors influencing help-seeking behaviour among teens

The propensity for young people to self-diagnose mental health disorders rather than to seek professional help has been attributed to numerous factors.5 These include individual factors (e.g., lack of knowledge about where to obtain mental health services, not knowing if symptoms were serious enough to warrant treatment), social factors (e.g., stigma and anticipated embarrassment, lack of motivation), relationship factors (e.g., perceived confidentiality and concerns about disclosing personal information), and systemic or structural factors (e.g., lack of time to attend appointments, transportation challenges, and costs).5 Together, these barriers to seeking professional mental health care could be compounding the reliance on social media outlets to both obtain information and to seek peer support and validation.

Individual, social, relationship and structural barriers may prevent adolescents from seeking professional help for mental symptoms

Practical recommendations

In response to the growing use of social media, clinical recommendations have been proposed by the American Academy of Pediatrics to guide healthcare providers and caregivers with respect to social media, including minimizing the potential negative effects of sick-role subculture on youth.2,6 These include asking about social media consumption and habits, providing psychoeducation to counter misinformation, encouraging parental viewing of content (both videos that are produced by children and/or content being consumed by them) and promoting ‘media-free zones’ such as at mealtimes and in certain locations (e.g., bedrooms).6 Ultimately, it is important for healthcare providers and caregivers to be aware of social media trends since they can influence mental health particularly among youth.2

Social media sick-role subculture remains an emerging and understudied phenomenon that clinicians should be aware of2

Our correspondent’s highlights from the symposium are meant as a fair representation of the scientific content presented. The views and opinions expressed on this page do not necessarily reflect those of Lundbeck.